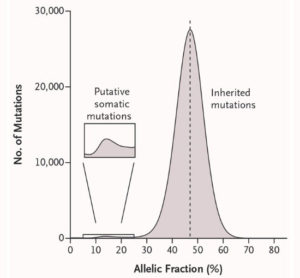

Genovese discovered somatic (acquired) mutations from their presence at unusual allelic fractions – reflecting that they are present in some, but not all, of the cells in a person’s blood.

Researchers have discovered an easily detectable, “pre-malignant” state in the blood that significantly increases the likelihood that a person will go on to develop blood cancers such as leukemia or lymphoma later in life. Giulio Genovese, Steve McCarroll, Ben Ebert, Siddhartha Jaiswal and colleagues describe this discovery in two back-to-back papers this week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Genovese noticed the phenomenon while analyzing exome sequence data from 12,000 Swedish research participants, half of whom were affected with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Genovese, who trained as a mathematician before becoming a geneticist, developed ways to identify the subset of mutations that a person had acquired during life, distinguishing them from the far-larger number of “inherited” variants with which a person is born (see Figure). He found that such mutations, rather than being randomly distributed across the genome, were concentrated in four genes – all genes known to be mutated in cancer.

Genovese hypothesized that the mutations reflected cells that had acquired some, but not all, of the mutations require to drive a cell to cancer. The cells, he hypothesized, were in a “pre-cancerous” state – vulnerable to becoming cancerous, but not there yet.

The key question, then, was what happened to these people later in life? Here, the research team drew upon a strength of the Swedish medical system –electronic medical records that allow health outcomes to be used in research, when patients have consented to contributing such data to research. Genovese’s colleague Anna Kahler at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm searched these records to find out whether the patients developed cancer in the years after their DNA was sampled for the original study. The result was astonishing – carriers of the clones were developing blood cancer at 12 times the normal rate.

The researchers also found that clonal hematopoiesis becomes increasingly common as we age: it is rare (<1%) among the young, but affects 10% of the population over 65 years old.

Jaiswal, Ebert and colleagues discovered the pre-malignant state independently while analyzing exome sequence data from patients with type II diabetes.

Toward early diagnosis and prevention of cancer?

Clonal hematopoiesis might be helpfully compared to colon polyps, the precancerous lesions that arise in the colon when a cell acquires a mutation that causes it to clonally expand. Hematopoietic clone, like polyps, are “precancerous” lesions that arise when a somatic cell acquires a mutation and clonally expands. The cells in polyps have a substantial risk of acquiring additional mutations and becoming malignant. For this reason, adults over 50 have been medically advised to get colonoscopies every 10 years; when colonoscopy identifies a polyp, it is often removed surgically. Such surveillance is reducing the incidence of colon cancer.

Could an analogous system now be developed to prevent blood cancers? “The challenge today is that unlike polyps, which are surgically removed to prevent colon cancer, precancerous blood stem cells are mixed up with the healthy cells,” McCarroll says. “We need to find medical ways to reduce the likelihood that these cells progress to cancer. That kind of research now becomes possible. It is a key research direction, as it could lead to ways for patients to benefit from information about their clones. Great scientists like Ben Ebert will lead the way in this important new research direction.”